U.S. grocery shoppers remain highly price-conscious, and 55 percent say tariffs are their top concern, according to FMI’s August 2025 U.S. Grocery Shopper Trends report.

The tariffs, however, have yet to be fully felt at the shelf.

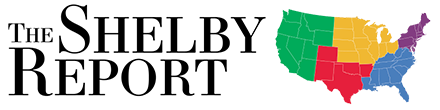

“Over the next three, six, nine, 12 months, we will see those factors filter into food prices pretty much across the board, not just on these categories,” said Ricky Volpe, professor of agribusiness at Cal Poly, referring to a country-of-origin map for several commodities.

Tariffs on metals like aluminum and steel are “where I see the real potential to impact food prices,” Volpe said. “There’s no getting around the role that inputs such as aluminum, steel and others, like copper, play in our food supply chain.

“When we talk about 25- or 50-percent tariffs on these metals, this means your cans of soda, your cans of beer, your prepared/frozen/microwavable products that have the metal casing or lid that gets peeled off – those represent substantial input costs for these products.”

Volpe and FMI’s Andy Harig, VP of tax, trade, sustainability and policy development, were the featured panelists for an Aug. 12 FMI briefing on food prices, trade and tariffs.

Harig said that while companies up and down the supply chain will be “asked to take a little bit of haircut here and there to mitigate some of the price increases, those price increases will make their way through” to retail.

One of the increases grocers will face is in cost for refrigerants, which often are produced in countries like China.

“That’s something that’s going to be difficult for a retailer just to absorb on their own,” Harig said, noting that food retailers’ profit margins average just 1.7 percent.

The bagel, dissected

When consumers look at tariffs, they see the percentages and may think, “‘Oh, my food prices are going to go up 15 or 25 percent,’ but that is, in fact, not the case,” Harig said.

A cinnamon raisin bagel was used to illustrate how tariffs could apply to its production.

“If we assume that bagels will continue to be made the way that they’re made in this picture, as this combination of domestic and imported inputs, then how will the price of the bagel change due to these tariffs?” Volpe asked.

The imported ingredients – wheat flour and cinnamon – are just over half the product’s makeup, and the average of the 15 and 20 percent tariffs on those ingredients, respectively, is about 18 percent.

“That means that the total expected increase in the cost of making that bagel will be closer to 9 or 10 percent of the value of the bagel, which, of course, is not insignificant,” Volpe said. “That is a cost increase that will very likely be passed on or transmitted to the food supply chain and result in higher retail bagel prices.”

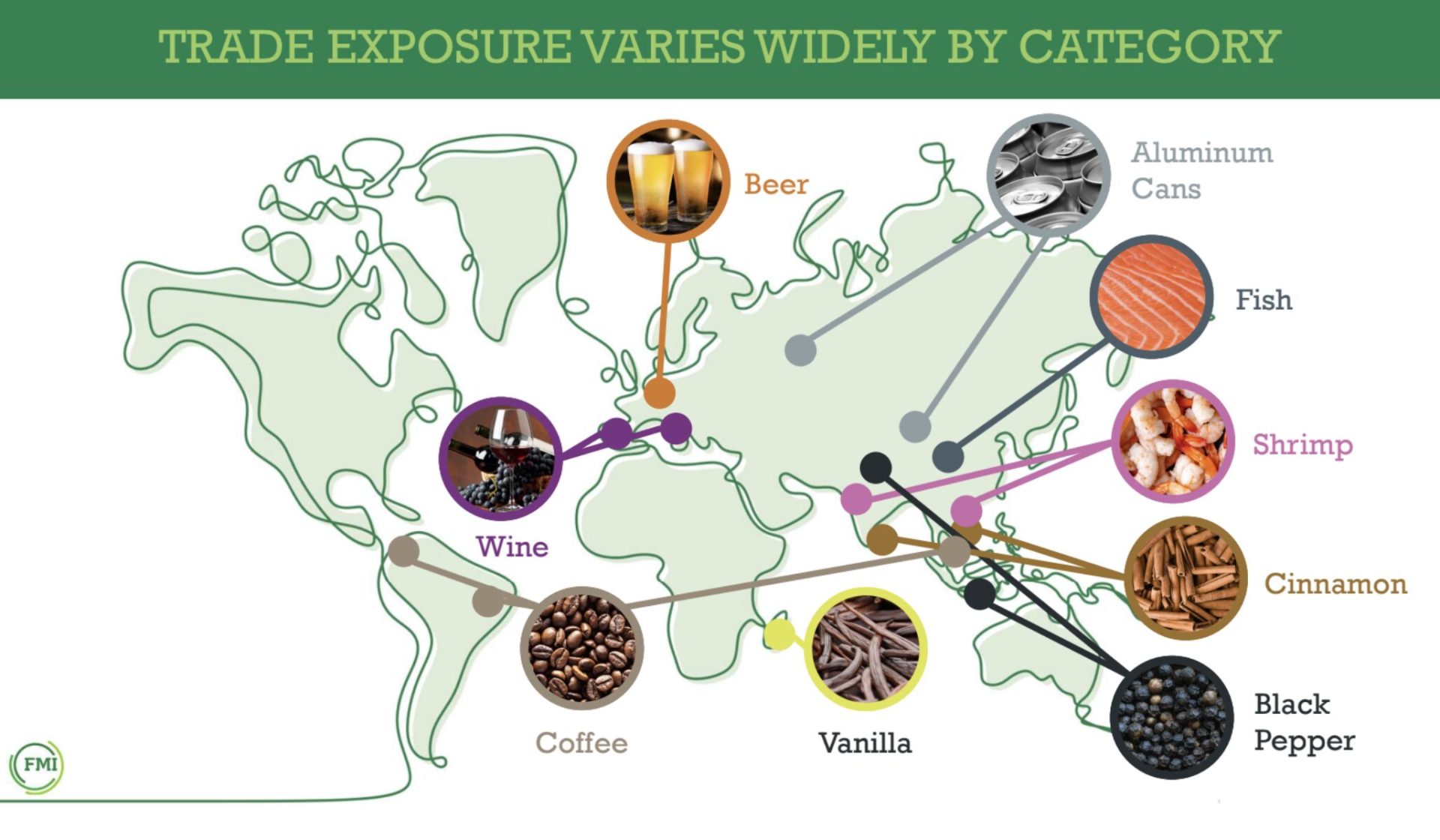

Tariff relief sought for things we can’t produce ourselves

Eighty percent of the U.S. food supply is produced domestically; the other 20 percent is “foods that, for the most part, really can’t be grown or produced effectively here in the U.S.,” Volpe said.

Cinnamon is one of the items that can’t effectively be produced in the U.S. due to growing conditions and thus is virtually 100 percent imported. Other items the U.S. is unable to mass-produce include bananas, coffee, mangos, cocoa and vanilla.

Imports also help fill seasonal gaps in U.S. production of fruits and vegetables.

Take cucumbers, for example. The seventh most popular vegetable in the U.S., cucumbers are regularly purchased by 64 percent of U.S. households. In 1990, about 30 percent of cucumbers were imported; today it’s about 90 percent.

“Cucumbers rely on a specific combination of heat, water, soil quality and soil pH, and those sorts of conditions are increasingly rare in the continental U.S.,” Volpe said.

Even California, where many specialty crops are grown, is not optimal for cucumbers so they typically are imported from places like Mexico, Central America and South America.

While the Trump administration has “talked a lot about how these tariffs have the potential to shift production back domestically and create jobs and support local economies and all that, that may work with some durable goods, but that doesn’t really make a lot of sense with cucumbers, as an example,” Volpe said.

For the U.S. to ramp up cucumber production to previous levels, substantial increases in greenhouse production would be required, which would mean higher operating and production costs vs. imported cucumbers.

“We estimate that the retail price of cucumbers in the U.S., at least in the short run, would at least double, if not triple,” he said. “And if our domestic per capita demand … remains stable, U.S. spending on cucumbers would increase by over $4 billion annually, comparing the prices we’re paying now to the prices we would pay growing them domestically at much higher costs. It’s emblematic of the challenges that food specifically faces for shifting production domestically.”

But Harig said FMI is looking forward to working with the administration to look at high-impact commodities that can’t be grown in volume in this country – or in Mexico or Canada, as most agricultural commodities from those countries continue to be tariff-free under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement that has been in place since July 2020.

“We’re going to continue to work with the administration to really figure out how we can create an exemption process that excludes those foods where tariffing them doesn’t benefit U.S. industry,” he said. “That could be products that are not grown in the United States, like cocoa, cinnamon and bananas, or it could be products that are inputs in U.S. production.”

The association is encouraged because of the trade deals already struck and the fact that “the president has a lot of authority to change rates within those agreements. The Secretary of Commerce himself even said, ‘No matter how much you tariff the product, there’s never going to be a U.S. mango industry.’

“It is not just a food system; it is a global food system,” Harig said. “We continue to support the president’s goal of strong trade deals, but we’re also asking that, as those agreements are finalized, relief be extended to essential food supply items in order to protect both affordability and supply.”

Speaking of supply, Harig and Volpe concurred that today’s store shelves are going to stay stocked, despite tariffs or other challenges.

“We really want to make it abundantly clear that regardless of whatever trade friction we see, the food supply remains secure,” Harig said. “The industry is adapting in real time. There might be some growing pains, but we’ll continue to work … to ensure our food supplies remain strong and safe and affordable.”