Arizona-based Bashas’ Supermarkets is celebrating its 90th anniversary in 2022. Bashas’ President Edward “Trey” Basha recently visited with The Shelby Report of the West’s EVP Bob Reeves about the history of the company.

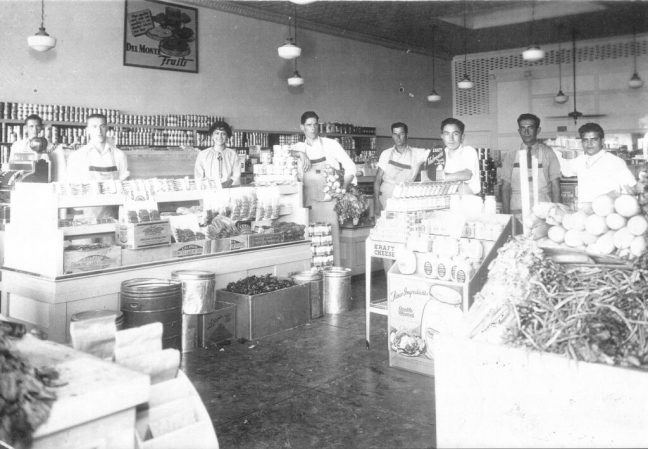

Trey Basha’s grandfather, Eddie Basha Sr., and his great-uncle, Ike Basha, both the sons of Lebanese immigrants, started Bashas’ in 1932 on Alma School Road in what was then Goodyear, Arizona. The town was the home of The Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., which was growing pima cotton in the area and also experimenting with rubber trees.

Basha said there were more people working there than lived in Chandler, Arizona, which drew his grandfather and great-uncle to choose it as the location for a grocery store.

“Some of their first customers were the Native Americans,” he said. “They brought their beef and their mesquite wood to trade for groceries. And we sold to the workers who were working here.”

That early relationship with the Native Americans was the foundation for the company’s future expansion serving the Navajo Nation, San Carlos Apache, White Mountain Apache and Tohono O’odhman Nations.

Basha said his great-grandmother and his oldest great-aunt spoke Pima, learning the language out of respect so they could communicate with the Native Americans who came in to do business.

“My great-grandmother was an amazing woman,” he said. “She spoke some Pima, she spoke English fluently, Spanish fluently and, of course, Lebanese fluently.”

From New York to Arizona

Trey Basha said his great-grandfather, Najeeb Basha, was in the import-export business with his father, who brought him over from Lebanon when he was 16. He met his wife, Najeeby, in New York City. They came from different towns in Lebanon, but many ethnic groups tended to live in “little enclaves” within the city, Basha said. That enclave is where his great-grandparents met and married.

He said his great-grandfather was doing well and would make unsecured loans to people.

“At one point in time, he and two other partners were considering buying Coney Island,” Basha said. “But his mother told him it would be a poor investment.”

When his great-grandfather’s warehouse burned down, he had no insurance and couldn’t collect on any loans because they were unsecured.

“He was left destitute,” Basha said. “They had nothing.”

His great-grandmother had a sister living in Congress, Arizona, which is near present-day Prescott. Congress was a mining town. The Bashas moved to the area in 1910 and opened two mercantile stores – which did not carry groceries – in Congress and another mining town, Basha said.

“My grandfather, Eddie Basha Sr., was the first Basha born in Arizona,” he said.

One night, a miner got drunk and burned down half the town, which included the Bashas’ store. The family opened a second store in downtown Chandler.

His great-grandmother, although proficient in languages, never learned to read or write in English.

“In those days, everyone bought things on credit,” he said. After the Basha children came home from school, they would go by the store and their mother would tell them who had come into the store and what they purchased, and they would write it down in the ledger.

After the death of his great-grandfather, his great-grandmother – the matriarch of the family – was left to care for several children, Basha said. They were inspired to get into the grocery business by observing the people going in and out of a grocery store across the street.

Around April 1932, Basha said Eddie Sr. and Ike opened the first true grocery store for the family, which they then started expanding south.

“My great-grandmother would drive the truck to the produce market in downtown Phoenix at 4 a.m. to buy produce for this store,” Basha said. “Everyone worked in the store, except my youngest great-aunt, and her job was to babysit my dad because my grandmother worked as a cashier.”

His great-grandmother, who lost her first child at a young age, had eight living children. Seven were involved in the business while the youngest, Zelma, who was also a budding artist, took care of Eddie Jr.

Grocery legacy continues

When Eddie Basha Sr. died at that age of 57 in 1968, Eddie Jr. took over the company, which had 16 stores at the time. Eddie Sr., who was “very entrepreneurial,” according to Basha, also had a dairy business. After Eddie Sr.’s death, the bank called all notes due, telling Eddie Jr. that his father was over-extended and they had no confidence in him.

Basha said a family friend, Adolph Weinberg, went with Eddie Jr. to the bank and co-signed all of the notes. Basha said Eddie Jr. worked through all of the issues and started to grow the company.

After noting a third-quarter drop in sales during the summer, Eddie Jr. and Ike began opening stores in the areas people went to during the summer – Sedona, Prescott, Flagstaff – to try to balance the volume, Basha said.

“He was very smart in that way,” Basha said. “He was also very good in real estate.”

Tough times

In 2008, the company was continuing to do well in the first half of the year. However, during the second half, “building here in Arizona dropped off a cliff,” Basha said. “It didn’t just slow down, it just ended.”

In October, Bashas’ called a meeting with its lenders and told them the company would be unable to make its covenants in 2009, he said.

As the U.S. went into a recession, the company’s largest vendors put Bashas’ on cash and prepay, which “took $20 million of liquidity out of the company immediately,” Basha said.

The company filed Chapter 11 in July 2009.

Basha said once the company entered Chapter 11, it was decided they had to make it work.

“We had thousands of people depending on us for their livelihoods,” he said. “We had people that we owed money to. We needed to make it work.”

He became the point person for the family. Prior to that time, he had been working with the company more in the legal and finance areas.

Bashas’ proposed a 100 percent payback to the vendor community, even though it was not required to do so. Basha said he attended a meeting with some of the company’s smaller creditors.

“We realized that they were hurting as well,” he said. “Arizona caught a cold, and we went on life support. A lot of the smaller vendors were really hurting. The larger vendors, they were going to sell their products – if we went away – through the rest of the competition. Some of the smaller vendors might not.”

The company paid back all its debts, with interest.

Looking to the future

After coming out of Chapter 11 and with all of the company’s creditors paid, Basha said the company’s ability to grow and expand was “hobbled.” The COVID-19 pandemic also brought home the reality of Bashas’ “being a small regional player,” limiting their ability to serve, he said.

“We weren’t getting the supply that a lot of our larger competition here was receiving,” he said. “So when Raley’s approached us, we had a fiduciary duty to accept that meeting, which we did.”

During the session, he said one of the first topics Raley’s President and CEO Keith Knopf talked about was how Raley’s takes care of its people and how the company serves the community.

“The first thing they put on the table was not their financial strength or their abilities, it was, ‘We take care of our people, we serve our communities,’” Basha said. “What we saw was a similar culture.”

He said they also saw a pathway forward for their employees and that the management group would stay intact. For Raley’s, the purchase was about adding scale, increasing capabilities and expanding its footprint.

“It was a very elegant solution,” said Basha, adding that several of the company’s shareholders preferred not to be in the business following the Chapter 11 filing and the focus on paying down debt.

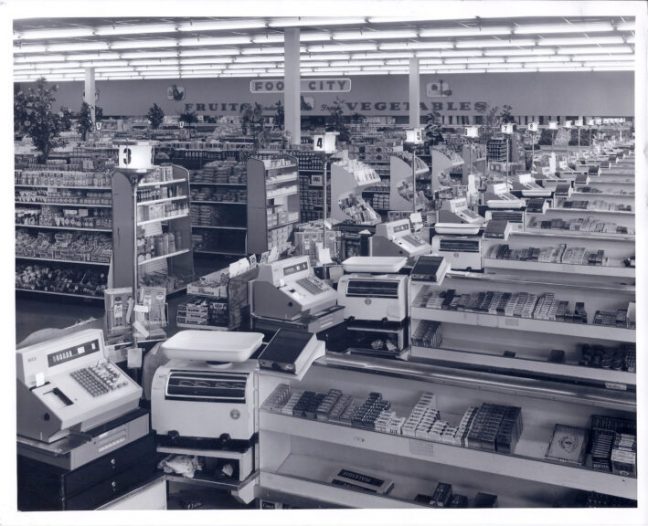

He added that Raley’s also committed to keeping the company’s formats – Bashas’, Bashas’ Diné, Eddie’s Country Store, Food City and AJ’s – and wanted to “keep and honor the Bashas’ name.”

For more information, visit bashas.com.

To view the full anniversary section presented by The Shelby Report, click here.