by John McCurry/contributing writer

While they are two different states, North Dakota and South Dakota share some challenges for their independent grocers. Distribution to retailers in rural areas and labor shortages are common problems for both North and South. Our market profile looks at the economies and state of the grocery industry in the Dakotas.

Efforts underway to address rural N.D. areas’ food store plight

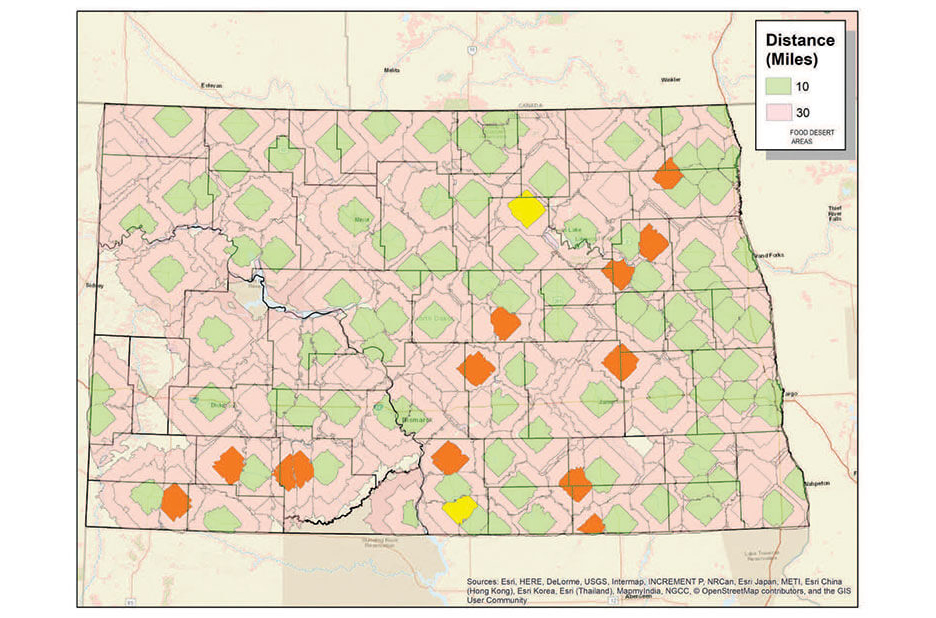

There’s a lot of brainstorming going on in North Dakota lately regarding the plight of the rural grocery store. Shifts in population, increased competition in metro areas and changing buying habits have put considerable pressure on the state’s small grocers, especially those in remote areas. The issue is becoming acute, and economic developers and legislators are seeking solutions.

Lori Capouch, rural development director with the North Dakota Rural Electric & Telecommunications Center, has been tracking the decline of grocery stores in rural areas over the last six years.

“We believe there are 97 stores now, but there’s no real reporting system so it’s however we can learn about stores struggling,” Capouch said. “Of those 97, 13 of them are operating as nonprofits or community-run. Another 13 are reaching out with financial concerns, and they are not sure if they will continue to operate.”

Capouch said as her organization gathers information, there is a realization that North Dakota’s rural areas are at a disadvantage, with grocery sales volumes dwindling and the customer base shrinking. The smaller the customer base, the higher the distribution cost.

“We are trying to find ways to streamline the distribution by helping communities purchase together and deliver food to a redistribution hub and then partner with someone to take it to the stores. We don’t know if that is the answer, and we are still trying to figure it out. If anyone has answers to these problems, we are certainly interested in hearing those ideas as well. We have five communities in the state where it looks like there are savings that can be had by purchasing collectively.”

Capouch said the thinking is that if just a slight shift of the way food is distributed can be accomplished, stores can stay open. Three of these communities have just one store and the others don’t have any.

Distribution of locally produced food also has its challenges in rural areas. Paul Overby, owner of Lee Farms, also is president of the Northern Plains Resource Conservation & Development Council, which conducted the Northeast North Dakota Local Foods Through Cooperation Feasibility Study, which was released at the end of 2019. It surveyed 10 counties with a total population of 66,593. The study describes the area as having a limited number of local food producers and venues in which to sell their products.

Overby said the study’s essential finding is that there is demand and growth for more local foods in the region but that existing producers don’t think they can expand, so it will take new producers or providers to meet that demand. He said his organization will try to identify how to assist existing producers overcome hurdles to expansion, encourage new local food producer startups and find new delivery methods to connect buyers and producers.

“This could conceivably also integrate with efforts to support small town grocers,” Overby said. “The council will have to use that input to decide what’s next. It doesn’t appear as if we need to focus a lot of attention on the demand side.”

Shawn Vedaa has been in the grocery business since the early 1980s and is currently owner of Velva Fresh Foods in Velva, a town of about 1,400

people 20 miles southeast of Minot. Vedaa is the only grocer in town. He’s also a state senator and a member of the Senate’s Interim Commerce Committee looking into the plight of rural grocers and how to improve food distribution. Vedaa is one of the sponsors of the resolution creating the study. The resolution states that since 2013, North Dakota has lost 15 percent of its grocery stores in towns with fewer than 2,100 people.

“Our big push is to get awareness out to the public that this is happening,” Vedaa said. “Typically, once these stores are gone, they aren’t coming back. With the decreasing population in these rural towns, stores don’t have the customer count they’ve had in years past.”

Vedaa notes that North Dakota law doesn’t currently permit grocery stores to sell wine and beer. Changing that law to allow sales may be something the legislature needs to consider, he said.

As for his own store, Vedaa is taking steps to keep it relevant to evolving customer preferences. He added a Hot Stuff pizzeria and deli about two years ago, and that has helped keep his customer count up.

Incidentally, Vedaa was a 2019 recipient of the National Grocers Association’s Spirit of America Award, which honors those who have provided leadership in the areas of community service and government relations on behalf of the food distribution industry.

Varied economies within the state

North Dakota Grocers Association President John Dyste sums up the grocery scene in North Dakota as a tale of two states: the metro areas are thriving, with robust options of modern grocery stores, while the rural areas have far fewer choices, with many stores lagging behind in modern equipment. He opined that North Dakota has a great business climate, buoyed by a thriving oil sector—the third largest in the country. However, there are certain rural areas in the state where the population is leaving and migrating to metro areas. That puts a strain on the small, independent grocers in these areas.

Competition is keener these days. Ever-expanding Aldi has one store in Fargo and plans a second by late this year. Costco, which has a store in West Fargo, plans to open a second North Dakota location in Bismarck this summer.

“The business is there; it’s just getting diluted quite a bit,” Dyste said. “There are so many places now where you can buy groceries. Dollar General came to the state about three years ago and now there are 40 or 50 of them across the state, raising some problems for rural grocers.”

Dyste said grocers in the metro areas have done a good job of upgrading their stores in recent years to attract customers. Conversely, many rural stores have outdated coolers and freezers that aren’t efficient.

“The ones who can keep up their equipment are in better shape, and the stores in the metro areas have all the bells and whistles,” Dyste said.

North Dakota hasn’t hopped on the plastic bag ban bandwagon that some western and eastern states have joined over the past year. In fact, the state took steps to keep local governments from enacting bans.

“North Dakota is a conservative state and not big on regulations, so the legislature hasn’t been overburdensome with regulations for a while,” Dyste said. “As a matter of fact, we were able to get a bill passed that does not allow cities or counties to pass local ordinances banning plastic bags and other types of containers. The fear was that if one town puts in a ban on bags and the next town doesn’t, it would cause problems.”

Also, there’s no momentum toward increasing the state’s minimum wage. The minimum wage issue routinely comes up every state legislative session, but to date, lawmakers haven’t determined an increase is necessary.

“I can tell you from experience that you can’t hire anyone for $10 an hour, much less $7.25,” said Dyste, a former grocer. “North Dakota’s economy is so strong that the minimum wage has no bearing.”

That tight labor market is the industry’s biggest challenge, according to Dyste. Grocers have increased wages and benefits but continue to struggle to find sufficient help. In fact, it’s such a big issue that the labor shortage is a primary concern that prompts some owners to sell their stores.

“Finding a meat cutter is very hard to do,” Dyste said. “I don’t think I could walk into a grocery in the state and talk to a manager without labor concerns being the first thing that comes out of their mouth.”

Looking at the positive side, Dyste said North Dakota still has a lot of strong independent grocers that operate efficient stores. Many grocers serve as community leaders, populating local school boards and city councils.

“The independent grocers have had to learn how to compete with the big box stores. The ones that adapt will survive and the ones that don’t will go away,” he said.

South Dakota Experiencing Slow But Steady Economy

South Dakota experienced slow but steady economic growth during 2019. Growth was about 2 percent. The state’s farmers endured a tough year, hit by a combination of bad weather and the trade war with China. Overall, the state’s economy ranked fourth in economic performance in 2019 among nine Mid-America States in the latest Creighton University Business Conditions Index.

“Based on recent surveys, I expect the South Dakota economy, for the first half of 2020, to rank first in the region in terms of economic performance with overall annualized inflation-adjusted GDP growth at 3 percent,” said Ernie Goss, director of Creighton’s Economic Forecasting Group.

The slow growth held true for grocers, said Nathan Sanderson, executive director of the South Dakota Retailers Association (SDRA).

“There are certainly independent grocers who are continuing to thrive, but the industry is also seeing changes that are coming nationwide,”

Sanderson said. “Larger grocers are offering in-store pickup or online ordering, that kind of thing. That trend is going to continue as we move forward. Grocers will continue to evolve as consumer preferences evolve.”

Population shifting

South Dakota, like many states, is going through population shifts. People are leaving rural areas for cities. Overall, South Dakota is a net in-migration state with the overall population increasing. The population shift is affecting grocers in rural areas, just like what is happening in the state’s neighbor to the north. Distribution can be a challenge for grocers.

“We have some very rural counties right along the Interstate and distributors getting to them isn’t a problem, but sometimes it is for others,” Sanderson said.

He added that the state enjoyed a good legislative session in 2019 from a business perspective.

“Taxes are low here, and it’s a really good place to do business,” he said. “From a regulatory standpoint, in 2020 we’re not looking for anything that would cause a major disruption.”

One pending bill would enact a packaging preemption, similar to that enacted in several Midwestern states, that preempts a municipality from taxing single-use containers. If passed, any future regulation would have to be statewide rather than piecemeal, Sanderson said.

There also are no pending minimum wage bills. Sanderson noted that the state approved a minimum wage escalator a few years ago. The rate raises to $9.30 in 2020, up 20 cents from 2019.

Labor challenges, local offerings

Finding sufficient labor continues to be the grocery industry’s No. 1 challenge since the state’s jobless rate hovers around 3 percent.

“It’s been a challenge for a while, and it’s a nice problem to have to some degree. South Dakota has had a low level of unemployment for a long time,” Sanderson said.

South Dakota was an early adopter of making local food available at grocery stores, so that national trend has not had a great impact.

“It’s interesting how things come full circle sometimes,” Sanderson said. “South Dakota grocers were stocking local food before it became fashionable to do so. Locally produced sweet corn and beef have been in grocery stores in the state for a long time.”

South Dakota has a substantial food processing industry. Two companies with recent expansions are Valley Queen Cheese and the Agropur cheese plant in Lake Norden.

Informed shoppers

Grocers are having to adjust to the ever-changing ways consumers approach their shopping. Consumers do more research these days before ever entering a store, Sanderson said.

“Consumers are far more educated about the products they purchase than they have ever been. That’s something that grocers are paying a fair amount of attention to.”

Sanderson said the prevailing attitude among the state’s grocers is one of cautious optimism.

“I don’t think many grocers anticipate a tremendous boom in 2020, nor do I think they are experiencing any significant downturn,” he said. “The trends we are seeing are not unique to the Dakotas or to the Great Plains. It’s the trends you see nationally of workforce issues and consumer choice. In the end, these are the types of challenges that grocers have been navigating for years and will continue to do so as consumer tastes evolve.”