In 1951, Harvey Mabry hit a grand slam in the semi-final game of the Little League World Series in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. He was 12 years old at the time and was the first Little League player to ever have accomplished such a feat in the series. Fans wanted Mabry’s autograph and, back in Austin, Texas, the team was welcomed home with a parade.

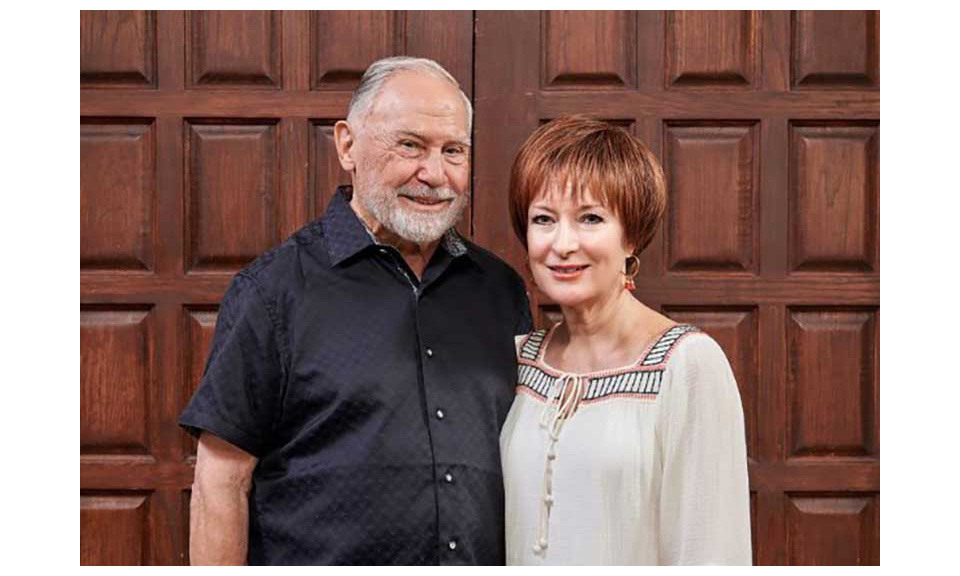

That was just one story shared by his wife, Marjorie, in a video tribute she had made for Harvey’s 80th birthday celebration, which was held on Aug. 11 in San Antonio.

For the record, Mabry also was the first-ever Austin player to hit a grand slam in any game leading up to the World Series, and no Austin Little League team has made it to the series since. A Stamford, Connecticut, team ultimately took the 1951 Little League World Series title, but that did not diminish Mabry’s achievement.

There in the dugout that day in Williamsport was the legendary American Major League Hall of Fame pitcher Cy Young talking baseball to Mabry and his peers on the North Austin Lions Club Little League team. Young and members of the team, including Mabry, would later be on the cover of Baseball magazine’s December 1951 issue (see photo).

Immediately following his triumph in Williamsport, star first baseman Mabry was invited to speak on a local sports radio program sponsored by the U.S. Marine Corps. He was asked whether he might join the military and answered that yes, he would, and he would be a Marine. A Marine who was present took the Eagle, Globe and Anchor emblem off his cover (hat) and gave it to the young Mabry.

Five years later, when he was 17, Mabry and friends were celebrating their high school graduation at the Austin Country Club. He and the four friends—two of them from the 1951 Little League team—went outside for a smoke and a beer. Their conversation turned to that World Series game and the radio interview that followed. The next morning, all five signed up for the U.S. Marine Corps at the recruiting office in Austin. They went in under the “buddy program,” guaranteeing that they would serve together during their active duty service.

In the Marine Corps, Mabry, who had a penchant for glaring at an umpire who called a strike on him as a Little Leaguer, learned to submit to authority.

An H-E-B lifer

Mabry began working for H-E-B even before he went to the Little League World Series. He was just 11 years old and worked at a location his father managed. Mabry bought his first car when he was 13 years old and too young to be licensed.

Because his Little League team went to the World Series, Mabry was guaranteed an offer from Major League Baseball upon high school graduation. He opted to stay with H-E-B after learning that the offer was for a D-league (rookie) team in South Dakota.

After active duty in the Marines, Mabry returned to H-E-B and became one of the first participants in the grocer’s management training program. He went to the University of Texas in Austin and began his “real” career with H-E-B. When H-E-B was awarded the Semper Fidelis Award in 2003 for its support of U.S. troops in Iraq, it was Mabry who accepted the award.

Mabry’s H-E-B career spanned 50 years. He twice tried to retire early and both times H-E-B Chairman and CEO Charles Butt changed his mind. Mabry did retire at age 66 and declined all offers for a celebration of his years of service. Butt called a meeting of executives at his house, which wasn’t unusual, and Mabry attended. That turned out to be his retirement party, with 25 executives he had worked closely with sharing kind words about him.

Mabry nails the pitch

In 1997, Shelby Publishing President and Publisher Ron Johnston wrote an article about Mabry with the headline: “Winning Attitude Began Early for H-E-B’s Harvey Mabry.” In it, Mabry is quoted as saying, “You can’t really overestimate the potential that an individual has. Everyone has a lot more there than probably they are being allowed to give.”

In June 2002, Johnston wrote another piece about Mabry, who then was president of retailing for H-E-B. Sixteen years later, Marjorie used part of that article in the video tribute for Harvey. Below is the part of Johnston’s 2002 story, “H.E. Butt’s President of Retailing Nails the Pitch,” she chose:

“H-E-B, a sponsor of the Astros over in Houston, was due for an executive to toss the traditional first pitch before a late-season game. The setting and the man chosen were perfect. The Astros were hosting the Chicago Cubs at then-Enron Field, with post-season play on the line. Amid the playoff atmosphere, a gentleman strolled onto the field who had known that feeling 50 years ago. Later, his family and friends told him of how the huge scoreboard had flashed his name and the PA announcer extolled his recent 50-year Little League reunion.

“Harvey never heard a word and barely could hear the huge applause. He was totally focused, blocking out all vision and sound except for that tunnel of sight heading from the pitcher’s mound to home plate. Then, just like 50 years before in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, Harvey Mabry came through. A smooth windup, a timely release and the ball was on its way, straight into the catcher’s mitt.

“‘I didn’t want to embarrass myself,’ he said to me. The thought never crossed my mind. You see, Mabry, just like at H-E-B, was prepared. Days before center stage in Houston, he found a high school baseball field near his home. Harvey marked off 60 feet, 6 inches from home plate and practiced every night throwing the ball over the plate.

“Embarrassed? Cy Young was beaming in baseball heaven.”

Keep reading:

https://www.theshelbyreport.com/2018/10/12/evo-hemp-expands-whole-foods-h-e-b/

https://www.theshelbyreport.com/2018/10/05/h-e-b-buddy-league-campaign/