Andy Kennedy’s session at IDDBA 2024 was designed to help his audience better understand the steps along the journey to FSMA 204 compliance. Kennedy has worked in traceability for the past 17 years, currently with New Era Partners and before that the FDA as well as technology and standards development companies.

The compliance date for FSMA 204 – also known as the FDA Food Traceability Final Rule – is Jan. 20, 2026. The rule, finalized in November 2022, requires companies that manufacture, process, pack or hold certain foods to keep additional records.

The foods subject to the rule are listed on the Food Traceability List (FTL) and include specific cheeses, eggs, cucumbers, herbs and leafy greens. The goal is faster identification and rapid removal of potentially contaminated food from the market, resulting in fewer foodborne illnesses and/or deaths.

Kennedy was with the FDA from 2019-22, “possibly the most exciting time to be at FDA … not only did we have a little bit of a pandemic in there, but we were also working on the food traceability rule, which was an amazing new development in the food traceability space that we’ve been working toward for many years.”

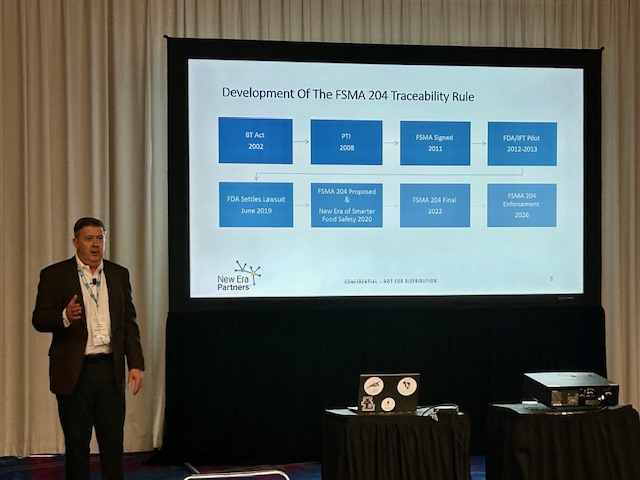

Food traceability became a topic of much discussion in the U.S. in the aftermath of 9/11. The Bioterrorism Act of 2002 was the first “big” traceability rule, he said, “and as its name implies, it really came about from the fear about contamination of the food supply chain.”

The rules were finalized in 2004 and went into effect the following year.

[RELATED: How To Get Ready For FDA-Enforced Food Traceability]

“That’s really the initial food traceability rule, and it still exists today,” Kennedy pointed out. “That’s another thing I want to emphasize – the BT Act didn’t go away just because of FSMA 204. FSMA 204 is about additional recordkeeping requirements. So, keep in mind that the BT Act is still in place for a lot of foods today.”

One change under FSMA 204 is that farms and restaurants are now required to comply. These two groups had been exempted under the BT Act, but outbreaks can originate at farms and diners have become sick after eating at restaurants. The FDA realized both groups needed to be looped into the new rule.

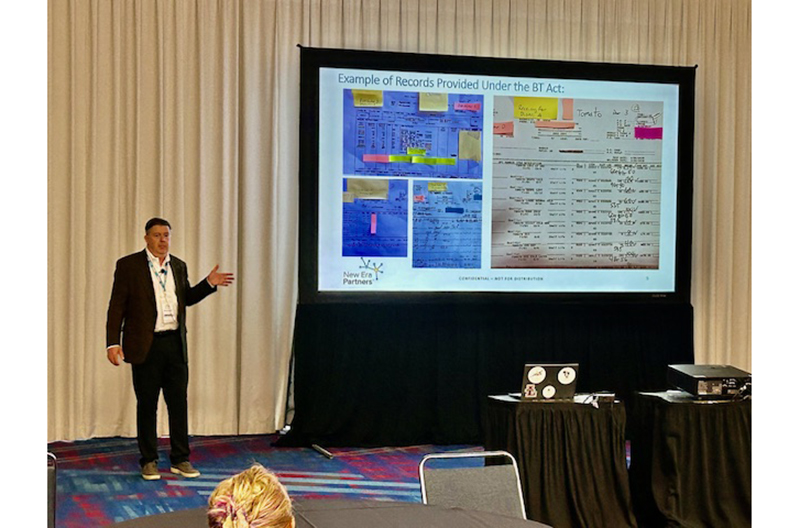

Also under the BT Act, records kept by members of the supply chain were not required to be shared with anyone else, so companies came up with their own.

FSMA 204 seeks to change that, to standardize the information along the supply chain. The rule applies to domestic and foreign companies that produce food for U.S. consumption – from the farm all the way through the supply chain to the consumer, whether in the home or restaurant. Should there be an outbreak, any information requested by FDA typically needs to be transmitted within 24 hours.

What is the information needed? It varies depending on the type of supply chain activities they perform with respect to a food on the FTL.

Any item on the FTL must be tracked throughout the supply chain: farmers/producers; manufacturers; distributors; and retailers or restaurants. Again, those items include specific cheeses, eggs, cucumbers, herbs, leafy greens and nut butters, among others.

These items are covered not just when sold on their own but also when used as ingredients in further processed items. If the item has not undergone heat processing – for instance, nut butter that is used in a raw energy bar or celery is used as a deli salad ingredient – records have to be kept for that item and supplied to the company doing the further processing.

While records can be kept manually – Congress stopped short of mandating electronic records or a specific technology to be used – electronic records make it much easier to comply with FDA’s requirement that records be provided within 24 hours during a foodborne illness investigation.

Rather than individual documents, FDA wants an electronic sortable spreadsheet for its investigation. Kennedy cautioned that when electronic records contain links, the links must work for two years.

Kennedy showed the audience an example of electronic sortable spreadsheet where each tab is a CTE, and each column contains KDEs.

“You can use whatever software version that you want,” he said. “It’s really up to you how you want to do it, but that’s the basic idea – ship, receive, transform are all individual tabs with the key data elements.”

When recording ship from/ship to, he said that information needs to be specific. It should be the actual physical location where the item is from or where it is going – not a corporate headquarters, for example, if that’s not where the item actually originated or is being shipped to.

On the product description, there are no hard and fast rules, but should include information like commodity, variety, pack size, pack style, brand – “that typical sort of information that from that description, you can figure out the product,” Kennedy said.

The product number could be linked to an invoice, a bill of lading, an advanced ship notice document, etc.

The traceability lot code is a barcode that identifies the source/manufacturer. This requirement is “next level,” according to Kennedy. “All suppliers have to identify the traceability lot code for that product. It has to be shared to subsequent recipients, captured and then passed along.”

For instance, the distributor receives the traceability lot code from the manufacturer and then passes it to the store or restaurant.

[RELATED: What Independents Must Know About FSMA 204]

As a manufacturer or food processor, the next big critical tracking event is transformation, he said. They must have a traceability lot code for any ingredient they are transforming.

“Any foods on the food traceability list that come in as an ingredient, you have to record the lot code, the product description and unit of measure for those inputs and for the outputs,” Kennedy said.

“If the finished product is on the food traceability list and the ingredient is on the food traceability list, you record input and output. For cheese companies, the input may not be on the food traceability list because it may be milk, and that’s not on the list. So you just record the finished product output.”

They need to record the location where they did the transformation, and then the date the transformation was completed. If it took multiple days, it’s the date of the last day. They then record the outbound shipping information to the distributor, who receives the product and does their record-keeping before sending it to the retail establishment.

For a deli salad, for instance, that contains fresh-cut onions and celery, the processor’s transformation record would have as inputs the two fresh items; the output would be the deli salad.

“And then the traceability record would be for the deli salad,” Kennedy said, and the processor would pass along the traceability lot code for the deli salad, not the components.

“You don’t have to pass all the lot codes for all the ingredients to your trading partner; you just pass the finished product.”

However, the processor does need to have that source information in their sortable spreadsheet that they would provide to the FDA if needed.

The generally accepted best practice within the food industry is to use the GS1 GTIN as the product identifier, “and then off that you hang things like the product description, the pack size, pack style, the brand owner. The lot number is the second data element.”

Both elements can be put into a single barcode so the receiver can scan that barcode and get both pieces of information.

Having user ID and entry date as data points are helpful, he added, so that you know who created the record when.

Enforcement to evolve

Kennedy expects the FDA to use 2026 as a “shakeout year” for enforcing FSMA 204. If there were an outbreak after the rule goes into force, they will ask for the sortable spreadsheet.

“If you can’t produce one, that’s when they’re going to communicate with you to say, ‘Look, this is a requirement under this traceability rule that you produce this in 24 hours and you weren’t able to do that, and we want to talk with you about that and explain the rule,’” he said. “You’ll get a warning to say, ‘Next time, we need these records in a sortable spreadsheet.’ But it’s a new rule, so they understand that people will be evolving their practices.”

As a result, 2026 could be characterized as a period of “educate before you regulate” for FDA. But as 2027 rolls around, FDA field inspectors likely will start enforcing it through the normal inspection process.

“They’ll look for other regulations, too; it won’t be like a standalone traceability audit,” Kennedy said. “They’ll go in and do an audit for food safety practices in general, covered under the various FSMA rules.”

While FDA doesn’t levy fines, it does have the power to shut down a business. Therefore, moving toward compliance as quickly as possible is a good idea.

Kennedy pointed out another motivation for compliance – one’s trading partners.

“Your trading partner has to receive that information,” he said. “If they don’t get your traceability lot code and source, they’re on the hook because they have to record that receiving information. So, actually, the bigger penalty is rejection at your at your trading partners.”