Alaska’s grocery industry faces a unique set of challenges. The vastness of the state, coupled with a relatively small and dispersed population, creates logistical hurdles for getting food onto shelves as well as higher prices.

This complex environment necessitates a diverse grocery landscape, with national chains, regional players and independent grocers all vying for a slice of the market.

A network of independents plays a crucial role, particularly in remote areas. These stores, often tribally owned or operated by local families, provide vital access to groceries in communities where major chains might not find a foothold. However, these stores often face higher transportation costs and limited buying power compared to their larger counterparts.

The Alaska Food Policy Council emphasizes the importance of supporting these independent grocers who play a vital role in food security, especially in rural Alaska, and contribute to the cultural fabric of their communities.

Mike Jones, research assistant professor of economics at the University of Alaska-Anchorage in the Institute of Social and Economic Research, serves on the executive committee of the Alaska Legislative Food Strategy Task Force alongside members from the Alaska Food Policy Council.

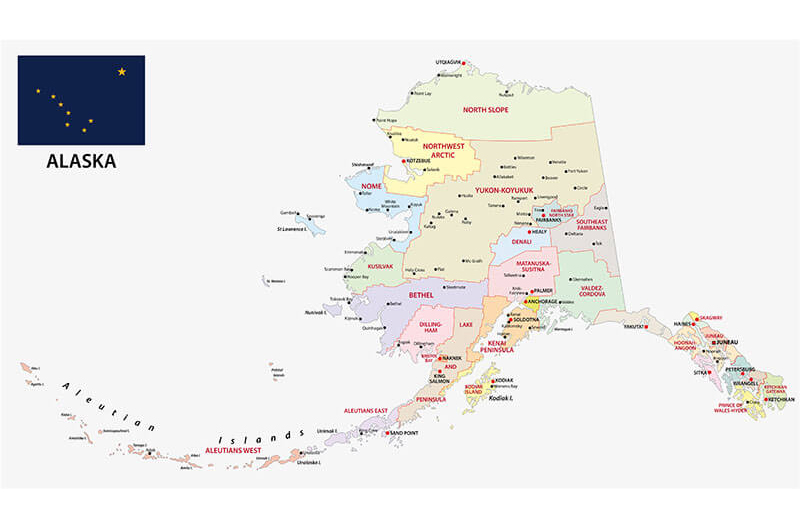

He noted that more than three-fourths of Alaska’s communities, comprising between 20-25 percent of its population, are off the road system.

“It is truly a multimodal supply chain to get food, particularly perishable food, to these communities,” he said. “And our climate is very harsh, seasonally. In the summer, Alaska is the best place to be in the entire world. It’s a tough place in the winter.

“In both the summer and the winter, you have a significant amount of spoilage of perishable goods, particularly produce, that is on its way to these remote communities.”

Many of them are heavily Alaskan native and have been there for an extremely long time, Jones added. The formal grocery retail sector has become an important part of how these communities get the food they need to live year-round and supplement wild food collection, which is mostly focused on protein sources of fish, predominantly salmon, along with moose, caribou and marine mammals.

Ruby Fried with the University of Alaska-Anchorage surveyed members of the Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association on what they think would improve access to food in their communities. According to Jones, four of the top five responses were having more healthy foods at the store, having more affordable store-bought foods, a decrease in the cost of shipping and more reliable transportation or delivery of food.

This survey showed that supply chain issues, particularly in grocery retail, are some of the most key to improving access to food in these communities.

Getting there

The vast majority of foods coming into Alaska arrive by boat, many at the port of Anchorage. Once the food arrives there, it then goes out for delivery over the road system or by air.

Of the communities that are not on the road system, the larger towns are considered hubs, with the smaller outlying villages as spokes. Those villages have populations between 50 to 1,000 people, Jones said, which is a common population range for the state.

To get food from Anchorage, there are a couple of options. Alaska has a specifically designated mail system, the Bypass Mail program, which bypasses the post office, Jones said. As an example, food can be dropped off at an air carrier, but the order has to weigh at least 1,000 pounds, he said.

“It’s meant to be bulk shipping, and it ships at a subsidized rate … It’s non-priority shipping, third-class mail, so priority mail will jump the line.”

Jones said this keeps things affordable, noting that a large part of the food shipped this way is dry goods. Any delays in shipping are less impactful on food quality for these non-perishable items.

Shipping perishable items, however, poses a different set of challenges. Jones said the Bypass Mail program carriers are not obligated to provide freezer or refrigerated space for shipments. He noted the mainline carriers, particularly in Anchorage, will have this capacity to store food until it is shipped farther along the route.

Food is flown out to a hub community via mainline aircraft. Once it arrives at the hub airport, it is exposed to the elements during the unloading process.

According to Jones, some carriers have better ways of protecting perishables than others, “but it’s very possible that produce sits on the runway in either extremely cold temperatures or summer temperatures for even a couple hours as the plane’s unloaded or loaded. And when it’s 30 below and produce sits on the tarmac for a couple hours, that’s really going to affect the quality of that food and may lead to total spoilage.”

If it survives that leg of the journey, it is transferred to a bush airline that specializes in small planes such as Cessna Caravans. These carriers are generally less capitalized than the mainline carriers, Jones explained, often with significantly less or even no cold storage capacity in their hangars. He noted they would have freezers before they would have refrigeration space.

These bush planes often wait until they have a sufficient load before they will make a trip to a village, which in some instances could take a couple of days. In addition to the load factor, these flights also depend on the weather.

Not only is Alaska weather very cold, Jones said it also is very cloudy. Under these conditions, planes often have to operate under instrument flight rules due to decreased visibility. To do this, pilots need a certified weather report.

Most of these reports come from automated weather observation stations, Jones said. Unfortunately, these stations often are out of service due to equipment failure or telecommunications outages.

“My research has been measuring these outages over time and space, and we see that the median outage for a full outage is about three days, but the top 10 percent of outages were over 25 days,” he said.

Repairing the equipment often requires a technician from the FAA. However, “sometimes they can’t fly to that community to fix the AWOS because the AWOS is broken. So it’s quite a catch 22 sometimes and a real challenge,” Jones said.

He noted the “very serious lack of redundancy” in those systems, adding there is a statewide push to address that problem and therefore prevent these supply chain delays.

“This really does become a food security problem because in these small villages if planes can’t fly – and that is the only way, especially in certain times of year, that people are able to access grocery retail goods is if they are flown in – then you can end up with empty shelves in grocery stores.”

These delays mean that spoilage is factored into the final consumer cost. As a result, consumers end up with less fresh produce that grocery retailers attempt to ship or less fresh produce that survives the trip.

“It’s built into the margin,” Jones said. “So rural Alaskan consumers have very high food prices – famously high food prices.”

As an example, he said a half gallon of milk that would cost about $2.80 in Anchorage or Fairbanks could cost about $6 in rural communities, particularly in the west and southwest. Infant formula that would cost about $18 in Anchorage could cost up to $30 for the same size in the rural areas. A five-pound bag of rice, priced at $5 in Anchorage could cost closer to $15 in many rural communities.

“Pounds equal cost in terms of air shipping as well,” Jones said.

Grocery retailers in Alaska do the best they can to get food to their customers in the face of “pretty serious structural supply chain issues,” he added.

A recent FAA reauthorization bill contains some 40-50 clauses that directly or indirectly apply to reforms for Alaska, some which allow for expanded redundancy in the AWOS and increased scrutiny over resolving outages more quickly, Jones said.

“I hope that some of these reforms and some key investments can help alleviate some of these data driven supply chain bottlenecks.”

At the request of the governor’s office, Jones said his team is auditing the cold chain storage capacity in hangars. He noted after visits to some of these remote communities, it was “pretty clear that the throughput does not have sufficient volume capacity for cold storage, particularly in a lot of the smaller carriers. We’re going to be quantifying that and trying to think about strategies to increase that capacity.”

[RELATED: Wild West Of Grocery: A Look At Dynamic Landscape Of Western U.S.]