Sponsored content

Utilize spare capacity on site by putting your investments to work

As a grocer, the majority of your costs are related to your goods sold, location, maintenance and labor.

When factoring in all these costs, opening or acquiring a new store can amount to anywhere from $1 million in small markets to more than $50 million in high-traffic areas. Once the store is up and running, grocers often spend more than 70 percent of their gross profits paying off these assets (mortgages, interest and rent) and operating the store (staffing, accounting and utilities).

Despite the considerable dollars grocers allocate to these parts of their business, few grocers measure how effectively these assets are being utilized on a daily basis. Every minute a checkout lane is left unstaffed because employees are stocking shelves is a minute you’re not using the resources you’re paying for – like the register and staff members – to their full capacity. And that leaves profit on the table. In fact, by making better use of your existing assets, you could see a profit that could cover the cost of hiring an additional team member to staff that empty register.

In the current economic environment, maintaining – let alone growing – bottom line profit is a challenge. The average consumer visits almost five different banners a month and, compared to pre-pandemic levels, 25 percent more of a consumer’s spend is going to their secondary or tertiary stores. Even market leaders are struggling to capture more share of wallet.

Unless you’re already capturing 100 percent of grocery spend in your markets, it’s important to pull new consumers in and motivate current consumers to add more to their baskets in the most efficient way possible.

We call this capacity utilization, and it’s a formula that can fundamentally change the way you think about your business.

Measuring capacity utilization

“Capacity utilization” is the measurement of how many transactions occur during a specific time frame, compared to the transactions that could have occurred during the same time frame if resources were fully utilized.

This measurement is tough for grocers to nail down because of the many moving parts: inventory, available registers, parking lot size, and, most importantly, labor. As you grow your consumer base, your biggest operating cost will be staffing your grocery store just to keep up with that growth. Labor is a considerable expense to consider, but by maximizing capacity utilization you will be able to cover those rising labor costs.

Let’s start by breaking down how we measure capacity utilization. At Upside, we calculate both average utilization, as well as utilization at the busiest times. Of course, there are days in the year when you serve an unusually high number of customers – like the week of Big Game Sunday and Thanksgiving – so we take those peak days into consideration (top-performing 10 percent) and remove them from our analysis as outliers.

- Average utilization: Looking across a 12-month period, we identify the single hour with the highest number of transactions to give us an idea of the maximum capacity of the store, and use that as the max capacity benchmark. Some stores go a step further to look at items per hour, or items per minute, to measure this max capacity benchmark, but Upside uses number of transactions to simplify measurement. We then compare this benchmark to every other hour the store is open, record the number of transactions and divide the total number by the max capacity benchmark to find the average utilization.

- Utilization at the busiest times: For this higher average, we take the three busiest hours on any given day and calculate the average number of transactions during those hours specifically, and compare it to the max capacity benchmark. This comparison shows whether utilization reaches its full potential during those spikes in traffic.

In an analysis of small, medium and large grocery store chains nationwide, we found the average store is only utilizing 24 percent of its capacity. During peak hours when stores are seeing the most foot traffic, utilization jumps to 46 percent. This means anywhere from 54-76 percent of store capacity goes unused.

That wide gap represents what stores are actively earning today versus what they could be earning by using their existing resources to drive customer spend away from competitors and into their stores. It’s a story of unused potential that grocers must figure out how to capitalize on.

Common approaches for increasing capacity utilization

Right now, you’re probably using a few different strategies to get more consumers in your store. Here’s why they’re not enough:

- Lowering prices is tricky with ongoing inflation – retailers are often forced to pass rising costs onto consumers, increasing the friction of choosing their store.

- Loyalty programs only reach a considerable portion of current consumers, but do little to bring in new ones.

- Third-party delivery services are effective at meeting consumers on their smartphones when they’re making purchasing decisions, but product fees eat into already razor-thin margins.

- Traditional and digital advertising costs are rising, and privacy laws around third-party cookies limit the ability to collect consumer data that can target potential new customers.

Current solutions rely too much on cutting costs and can do more to efficiently change consumer behavior. Grocers need to look beyond traditional tactics and think of ways to create conditions that will maximize their capacity utilization.

The financial impact of increasing capacity utilization

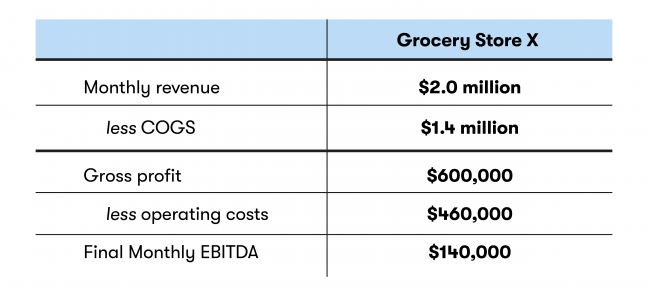

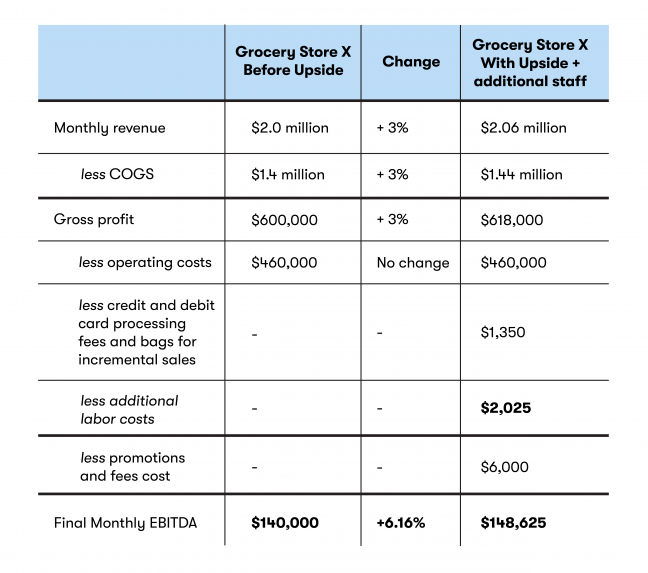

Let’s take a look at an abbreviated monthly profit and loss statement from grocery transactions at an average grocery location.

Here’s how this store was faring:

How does capacity utilization play into this?

Imagine if you could get each consumer to put just one more item in their shopping cart during a grocery run. Or if you could identify consumers shopping with nearby competitors, and get them to shift their purchase to your location. This extra purchase would fall straight to your bottom line since it would come at no additional cost to your store beyond the cost of the good itself.

So why does implementing a concept this simple feel so complex?

Instead of considering these profits and losses at a store-level, retailers need to think about profit and losses at the customer or transaction level. This means moving away from broad-based tactics that touch the entire user base, and instead identifying the consumers they don’t have today on a one-on-one basis to get them to their stores in a profitable way.

This is why we designed Upside to:

- Expand your store’s reach by identifying untapped customers who have yet to visit your store.

- Measurably change consumer behavior to bring new, incremental transactions and higher spend in a way that’s profitable for you, the grocer.

- Drive consistent, incremental revenue to your store through higher capacity utilization by making ourselves – and your business – a larger part of even your most frequent consumers’ routines.

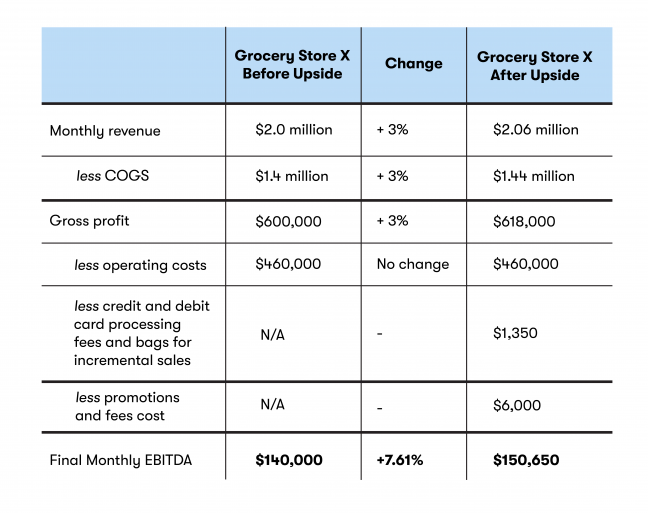

Upside provides our merchants with a 1-3 percent lift in total revenue on average within the first 12 months of launching, which in the case of this example, elevates the Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization (EBITDA).

Here’s that store after introducing Upside:

With this increase in profit and new customers, you may be wondering how your staffing would keep up with larger demand. Many businesses find that they have underutilized labor, and they can shift to fill increased demand. But even if you are understaffed, the increased margins that Upside provides allow you to hire as-needed and still earn a profit.

Assuming a new field employee spends half their time working as a cashier and the other half stocking shelves, if they can process an average of 30 carts per hour, we estimate they can each check out $96,000 in revenue per month.

This means for every $96,000 in incremental revenue, you need to hire a new staff member to work 160 hours per month. If you pay a fully-loaded hourly rate of $20.25, this would translate to $3,240 in new operating costs.

In our prior example, we drove a 3 percent increase in revenue, equal to a $60,000 boost. This would require a retailer to staff an additional 100 labor hours, or add $2,025 in operating expenses monthly:

Depending on the state of your labor market (as many businesses are struggling to hire), you can elect to offer a higher, more competitive wage upfront. Luckily, as these calculations show, even a 20 percent increase to a $24 fully-loaded hourly rate would increase labor costs to $2,430 and still provide an EBITDA growth of 5.87 percent. This figure could even be distributed so you could hire staff at a slightly higher rate (say $21 to $22 an hour) and pay out raises to existing staff.

If you can split the difference correctly, you can bring in new profit, attract new talent and reward your team all at once.

Upside’s success with Grocery Store X proves that thinking about your business in terms of maximizing your capacity utilization can lead to results that wildly exceed your expectations.

As costs continue to rise and economic uncertainty changes consumer behavior, tracking and filling unused capacity in-store is the key to boosting profitable same-store sales.

For more about our capacity utilization formulas or to see how Upside can work for your business, visit upside.com/business/grocery.